The Importance of Inferring Intention

Our skills at inferring intention are underrated and need to be improved

In which I outline a framework for legibly, reliably, and modularly improving our innate capacity to infer our own intentions as well as the intentions of other agents we interact with. This framework has yet to be implemented or validated, but if successful will act as both a pedagogical tool for improving our intrinsic innate ability to infer intentions, but also as a type of prosthesis, like a pair of eyeglasses, to help us navigate the web of intentionality that surrounds us.

The concept of intention points to the capacity to perceive and act in relation to intrinsic values. As part of our subjective landscape, intention is never fully explicit. Indeed, intention is often internally implicit, and may only occasionally rise to conscious awareness. Our emotional landscape points to our capacity to form and hold intentions as much as our conscious awareness does. There is nothing incompatible about holding multiple intentions, for we can want to become multiple things simultaneously. In fact, there is nothing preventing us from holding incompatible intentions. History is littered with examples of how we can fail to realize our intentions are incompatible and therefore perform self-defeating, aborted, and/or ineffectual actions. As social creatures, humans have the capacity to internally model themselves and their peers to varying degrees of accuracy. One skill this enables is that we are able to infer intentions. I propose that inferring intentions is an essential skill for our past and future success as a species as well as for sustaining the beauty and habitability of our living planet.

As society becomes more interconnected, digital, and pluralistic, reliably inferring intention becomes ever more important. Because we interact with a larger number of beings than ever before, our innate ability to infer intention has become saturated. Paradoxically this both increases distrust and gullibility across our social landscape. Our capacity to appropriately modulate between suspicion and trust has been overwhelmed. I propose that our internal models of self are radically incomplete and insufficient. Collectively, we seem to overly stereotype each other as friend or foe. Equally worrisome, there are many important players in our world that we fail to recognize as having intention, such as corporations, governments, ecosystems and other forms of collective organization. In this latter case we do not even apply appropriate stereotypes and are incapable of inferring intention to their actions, even when such intention is actually present.

I believe the state of our technology and knowledge is advanced enough to start to create cognitive prostheses that can help us to reliably infer intentionality. If possible, this would have dramatic effects on our capacity for collective sense-making. Whether such prostheses are a physical technology like eyeglasses or a psycho technology like writing or something in between remains to be seen. Once applied, such technology would help us to remove much of the “fog of war” in identifying allies and enemies within our natural and social landscapes. If we could infer intention more reliably, then the downstream impacts of naive gullibility and distrust would be reduced. By reliably inferring intentions, we could quickly identify incompatibilities in intention and therefore have less reason to fall into sunk cost fallacies and resort to violent conflict as our positions become entrenched. Additionally, through quicker identification of the “lines of conflict” where we can see the greater social landscape of those who hold compatible and incompatible intentions diplomatic resolutions to our conflicts becomes more probable. We would be able to remove much of the guesswork in coalition building and creating mutually acceptable negotiation proposals. Finally, if we collectively become more aware of intentions, then through careful study we can start to accurately predict their consequences, as together we learn how intentions harmonize and conflict with one another within particular contexts.

By reliably inferring intention I am pointing to the quickness, accuracy, and comprehensiveness of our innate capacity to infer intentions. All three characteristics must be improved given the sheer number of entities exhibiting agency we encounter compared to what was present during our prehistory when we evolved our innate capacities for intention inference. Our physical and digital world is littered with objects that are imbued with intention. Each human made artifact, whether garbage or treasure is imbued with a whole trove of intentionality. The junk food wrapper on the ground speaks to the innate body’s craving for calorie dense foods; it speaks to the company’s intention to produce what sells and not necessarily what is good; and it often speaks to the consumer’s lack of conscious intention. The natural world is just as filled such artifacts of intention, for example the soil on which we tread speaks of the intentions of ecosystems to grow, eat, digest, absorb, renew.

Intentions, properly traced, are a proper efficient cause for understanding our animate and material landscapes. I propose that our ability to model intention likely binds us to particular places and people as much as our affinity or affection for them. When we are capable of reliably inferring intention, the world is imbued with greater degree of comprehensibility. Might this help explain why some people seem stuck in abusive or ineffectual relationships even when they are aware of how things could be different? If we could readily find the through-line of efficient cause back from action or object to intention, then our level of comfort and expertise with the world at large is sure to increase. By better inferring intention, we are therefore priming the world to be a more comprehensible, happy place. Not only will it make more sense, but our gullibility is bound to also decrease.

One is less gullible when one can reliably infer intention. Gullibility may result in entrapment, where an agent is lead into a position that they believe is in their advantage but actually enables another to take advantage of them. Such situations occur when there is an asymmetrical understanding of intention between the interacting agents. Would a fish catch a lure if they knew of the intention that placed it there? If we are to reliably infer intention, not only must we be able to better model the intention of agents, we must be more competent at generally inferring agency within the world.

There are more entities in the world with the capacity to hold intentions than individual human beings. Social organizations such as governments, families, and companies hold intentions; living organisms, both on the species level and individual level, hold intentions; ecosystems and other commons can even hold intentions. To hold intentions, the only properties that an entity must be able to represent are an awareness of their current state, their “cognitive being”, a desired state, their “cognitive becoming”, and an ordering between those two states. Different entities have radically different capacities in their ability to conceive of being and becoming, but for the purpose of inferring intention their actual cognitive state is not important. Instead, so long as our representation of their inferred intention demonstrates higher causal emergence than a control scenario, it is advantageous to treat that entity as an agent.

Causal emergence as a concept was coined by Erik Hoel and his coauthors and shows how in certain cases higher scale representations of a system have more causal predictive power than their underlying lower scale representations. So what I’m proposing is that certain collectives are best described using a higher scale representation of agency, and that representation has more causal power than viewing the collective as the sum of its parts. Indeed, if in reference to causal emergence, collectives are in some cases best described as individual agents, the reverse may be equally as true. Are there cases when individual agents are better described as collectives? I propose so, and the efficacy of psychotherapeutical approaches such as Internal Family Systems supports this proposition.

Our limited ability to reliably infer intentions is interfering with our ability to live together harmoniously. How then are we to proceed? The only generally acceptable answer, so long as we assume that the world does not decrease in speed and interconnectedness, is to individually and collectively become better at inferring intention. So long as we live in a globally connected pluralistic and digital reality, our innate capacity for navigating the landscape of social behavior is not up to the task. We must improve our collective capacities for intention inference. Unfortunately our ability to understand even our own intentions is limited. We cannot keep blindly trying to improve this innate capacity. The pace of societal and technological progress is too great for our natural and mimetic evolution to accommodate our present need.

It’s likely that to make progress we need a robust theoretical foundation upon which to scaffold a suitable model of intention formation. This presents a problem, as intention points at a component of cognitive processes and therefore lies within subjective reality. It is therefore not conducive to study within the current paradigms of “hard” science. Intention is a phenomenological state. It is part of our cognitive landscape and when it is legible at all, it is only intrinsically so. By legible, I mean it must be inter-subjectively understandable, just as language is. This produces a daunting technological and philosophical challenge, for to start structurally addressing this issue we need to legibly model the structures and relationships from which intentions emerge.

Legibly inferring intention likely doesn’t require resolving the hard problem of consciousness, but it appears to be uncomfortably close. Intention can be subconscious, and if we were to imagine there exists a clear divide between objective and subjective reality, then intention must “live” close to the fulcrum of that divide but clearly within the subjective side. Can we make progress without having a well-validated theory on the nature of subjective versus objective reality? The need to better infer intentions is very real and very pressing, and intentions lie somewhere in that particular Gordian knot so let’s hope so.

To my knowledge, there are no existing projects oriented towards improving our capacity for reliably inferring intentions. I believe this needs to change. If there are existing programs of this nature, I want to help in whatever way I can. Until I find such work, I will focus on trying to lay the groundwork of what such a program might look like. I will attempt identify the principle constraints to improving our innate capacity for inferring intentions and provide a rough proposal for a program oriented towards improving our collective capacities in this regard.

In general, it is hard to determine whether a successful resolution to the problem of reliably inferring intention calls for better theory or better design. Our existential need is not to recreate cognition, but rather to enhance our innate capabilities such that they are up to the task of sense-making within our globally interconnected pluralistic and digital society. As such, we need a framework for improving our innate capabilities, not a program to design new ones.

To infer intention for an agent, one must simultaneously have awareness of the objective facts surrounding that agent that are relevant to its intentions while also consolidating and extrapolating from those facts into a likely set of intentions that the modeled agent holds. In order to improve on our innate capacity to infer intention, the whole process from identifying facts, extrapolating from those facts, through inferring from those extrapolations must be legible enough that the person using inferred intentions stays in control of the underlying process. If they are ot in control, we are not improving our sense-making capacities, we are replacing our agency with self-mimicry. What we need is a legible framework that can help us to identify what intentions an agent likely holds, how strongly they likely identify with such intentions, and why it is likely that way.

As you can tell, nothing about this process can be definite, but that does not mean it cannot be informative.

Intention is a cognitive, but not necessarily conscious process. Intention forms at the intersection between cognition of where-one-is with where-one-wants-to-be. As such, it occurs though intrinsic consilience between Is and Ought. I propose that for intention to be legible, we must initially distinguish between these two types of knowledge, propose useful structures for expressing each type of knowledge in relation to the agent itself, and then separately address how the two sets of knowledge might recombine in order to generate intentions.

As mentioned before, each portion of our intention inference framework must be legible, but similar to our actual processes of forming intentions, it must also be dynamically responsive to what is relevant to the modeled agent itself. Cognition in general does not need to be legible, but any framework for improving our capacity for effective intention inference must be. Intention inference is a critical component of our decision making processes. To rely on an illegible tool for critical decisions would be an untenable proposition. It would be an extreme case of the gullibility trap, as we would be trusting an important piece of our social agency to a system that remained opaque to our understanding. Additionally, our capacity to incrementally improve the framework would be limited. Without legible waypoints, sub-components of intention-forming could not be expressed or isolated. One would have to internalize the entire structure in order to comprehend or improve it.

This constraint, inferring intention through legible processes is what muddies the water between theory and design. What we need is a method for individuals to become better at intention inference, but in order for the method to be successful it must predict intention in a testable manner that exposes the sub-constraints and forces behind those predictions. Neither our innate capacity to form personal intentions nor infer intention in others has this constraint. As such, this is a call to design a framework for legibly inferring intentions, not a theory of intentionality per se.

Note that the legibility constraint rules out most existing implementations of deep learning. The internal structure of deep learning models are marginally interpretable if at all. In general all we can assess is the relative accuracy of their generated results, and we should only perform such an assessment given adequate understanding of the assumptions and constraints behind the model’s training data. Also, the current paradigms of reinforcement learning suffer from problems such as catastrophic forgetting, which make it hard for them to dynamically respond to changes in relevance through incremental learning.

In order to infer intention, this framework must be based on a sufficiently justified theoretical foundation that we can expect to produce accurate inferences. As noted by John Vervaeke and co-authors, the primary constraint for what divides successful processes of cognition from unsuccessful ones is their relevance to the success of the agent. As such, the concept of Relevance Realization, introduced within the paper Relevance Realization and the Emerging Framework in Cognitive Science in 2009, marks a promising starting point for a framework for intention inference. On its own, it does not present enough explanatory power to show us what such a system looks like, but it does show us how the constraints of cognition are different than computation. To summarize, to realize relevance a cognitive agent must constantly tune themselves to the needs of limited computational power, finite decision time, and the dynamic nature of their relationship with the environment. They must constantly trade off between incompatible extremes. In this paper, the authors identify four separate types of optimization problems that a relevance realizing system must solve: Exploration-Exploitation: whether to exploit current opportunities or search for better ones; Specialist-Generalist: whether to devote resources to special-purpose machinery or general-purpose machinery; Focusing-Diversifying: whether to focus on a few physiological needs at the expense of others or to attempt to satisfy all needs equally; Efficiency-Resiliency: a higher order trade off on whether to maximize efficiency in the current ecological niche or maintain resiliency to changing environments.

Although Relevance Realization theorizes a type of computational relationship that might satisfy these identified constraints to cognition, they lack a testable hypothesis on how that type of relationship might be implemented. There’s a promising complimentary framework, predictive processing, that attempts to mechanistically explain the generative structure of cognition. Indeed, predictive processing overlaps with Relevance Realization in important ways. What predictive processing offers is a theory on how the same cognitive structure can propagate errors bidirectionally in a modular learning system, resulting in improving interconnected specialized and general cognitive systems simultaneously. Also promising, there are multiple computational models that implement predictive processing, also known as predictive coding. Indeed predictive coding may avoid many of the central issues of reinforcement learning approaches for machine learning tasks.

Although far from comprehensive, the above theories are a promising foundation towards designing a mechanism that might successfully mimic the relevance realizing potential of natural cognitive processes. If constructed appropriately, they may serve as the basis for a modular framework of intention inference. A modular framework is useful for a variety of reasons, as modularity enables us to learn and evolve in chunks rather than attempting to comprehend the entire problem all at once. Modularity is therefore useful both for pedagogical reasons, as well as technological ones. With a modular framework for reliably inferring intention in place, the same system would be able to assist us in training and exercising the skills necessary for reliably inferring intention while also enabling us to iteratively evolve external ‘intention vision’ instruments, that might augment our innate intention inference capacities similarly to how we augment our innate vision with eyeglasses, telescopes, microscopes, etc.

As previously stated, identifying a theoretical basis for how to accurately infer intention is only half of the problem. The other half is that intention inference must be legible in order for it to be useful for critical decision making. Fortunately there are promising theories that can help guide us here as well. In addition to Relevance Realization, Vervaeke et al have theorized on how cognitive beings rely on at least four types of knowing, the participatory, procedural, perspectival, and propositional. These ways of knowing are likely non-legible within actual evolved cognitive systems such as ourselves, but for our purposes they can serve as the basis of meeting our legibility constraint. If we are able to define the fundamental grammar of each way of knowing, then we may be able to inject legibility within our system of inference. If we can populate “realms” of knowing according to their grammar using relevance realizing processes tuned for a specific modeled agent, could we then legibly infer that agent’s intentions? If so, how might these separate bodies of knowing relate with one another? Are they all intermixed or is there a distinct ordering between them?

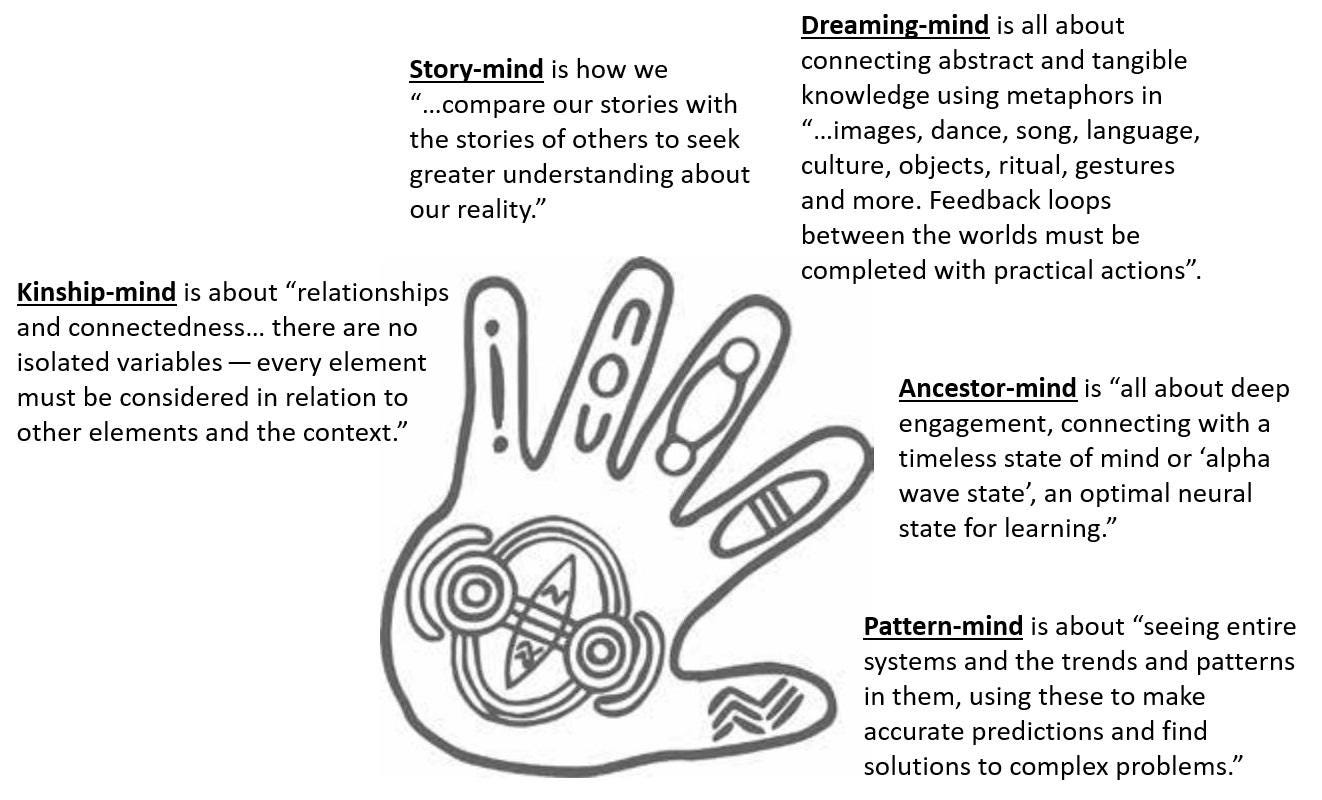

There are myriad types of cognitive functions that must be performed to infer human equivalent higher-level intentions. I propose that each of these cognitive functions must map to some system that can ‘realize relevance’ in its own right, such that the higher order relevance realizing agent is composed of a generative structure of relevance realizing subsystems. To infer intention, either pedagogically or technically, we must approach each such subsystems in a modular fashion. Might there be a means to structure them in an interpretable way? Here I draw on the idea of “the five minds” expressed by Tyson Yunkaporta in his book Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. These five minds help us to delineate between the interrelated functional modalities we utilize to comprehend our world. On their own, each of the five minds is insufficient to fit us into the world, but together they can. The minds are represented by the digits of a hand. Each one does not have much power or adaptability on its own, but their various combinations enable us to fit the contextual niche that exists between agent and environment. As shown in the following diagram, excerpted from the book, the five minds are described as follows. Although they may seem esoteric at first, I believe they each represent a unique type of function that in combination with the four types of knowing may carve cognition at the joints in a manner sufficient to enable us to begin a program to create a modular, legible, reliable framework for improving our innate capacities of intention inference.

The five minds as represented by the digits of an open hand

As previously mentioned, intention forms at the crux between a sense of being and a sense of becoming. In relating the two, a cascade of intentions and sub-intentions is generated, guiding our cognitive and physical embodiment into sequences of action and attention.

Because reality is in a state of constant flux, no entity has the option to stop evolving, but given agency, an entity can guide their becoming away from undesired states and toward desired states of being. If we assume that intention is a cognitive process that selects what to become given a current state of being, then paramount to the agent is that they simultaneously maintain awareness of their current state of being as well as any relevant information about notable “possible becomings” that may be relevant to their current and future states of being.

This presents two different types of computational problems. On the “cognitive being” side of intention, an agent must expand limited sensory information into a highly dimensional model of their relationship to their environment. The theme of cognitive being is that of information expansion. To adequately model the self’s state of being, the principle problem is filling in the gaps from incomplete inhomogeneous data into a coherent picture of how the self currently relates to the world at large. That picture cannot be static, but must be amenable to changes in perspective and relation, for to have intention we must be able to imagine what our future state might look like.

On the becoming side of intention, an agent must dynamically maintain a map between relevant plausible states of being and relevant associated states to be sought or avoided from that state of being. Learning such a system of association is a problem of compression, of finding signal in the continuous stream of sensory input that should be learned for better intention forming in the future. There are infinite possible future states, but not all of them are relevant to the agent. The agent must actively manage what they ignore such that they are selective about what they pay attention to. The concept that points most closely to this cognitive function is that of normativity. The cognitive structures of becoming define what “ought” and “ought not” to be in relation to the agent itself.

There appears to be a relationship within the four types of knowing and the five minds that structures them to produce legible states of cognitive being and cognitive becoming. When pieced together, as seen in the following figure, their structure coincidentally resembles a head and neck. Each realm represents different ways of knowing, while the minds populate the places in between. This structure is both modular and potentially legible and therefore sets us towards a path of incremental, pedagogically relevant, validatable advancement in our capacities for inferring intention.

The five minds interrelate with the four realms of knowing in order to form agential intentions and actions

Within the figure, the pattern minds find reliable motifs and structures within sensed objective phenomena and translate them into the common language of the intrinsic within the participatory realm. All further cognition, whether oriented towards the relatedness of being or the normativity of becoming relies on this common participatory symbolism. In this manner, the legion of processes necessary to enact all cognitive functions can interrelate based on a common language.

Between the participatory realm and the perspectival realm lie the kinship minds. These minds construct relational webs within the perspectival realm from the strands of information they gather from the stream of participatory communication. They also translate changes in perspective brought from cascading intentions into messages within the participatory realm such that pattern minds can then form them into objective phenomena.

Between the perspectival realm and the imaginal realm are the dreaming minds. These minds are responsible for transforming existing relationships into myriad potential forms and representing those potentials within the imaginal realm. Their symmetric function is to translate intentions born in the imaginal realm into a distinct forms and relationships and representing them in the perspectival realm.

Between the participatory realm and the procedural realm are the story minds. These minds structure symbols into functional sequences, saving certain sequences as procedures when they hold intrinsic relevance. When intentions form, they tell the corresponding stories, thereby populating the participatory realm with the messages that will properly yoke action to intention.

Between the procedural realm and the imaginal realm are the ancestor minds. These minds extract archetypes from stories and fit them into the diversity of relational potentials generated by the dreaming minds. The ancestor minds map essences to structures. They know the stories that each relation might tell if given the right context. When intention forms, ancestor minds prime the sequences of stories necessary to birth intention into action.

Notably, there is no propositional realm. Propositional knowing is inherently contained by the act of constructing an extrinsic framework around intentions and therefore its essence imbues the entire program. Propositional knowing functions as part of the mechanism that allows us to separate the realms of knowing from the minds. In its place I have located the imaginal realm, a term coined by the philosopher Henry Corbin in 1964 in the paper Mundus Imaginalis or the Imaginary and the Imaginal to represent this theretofore untranslatable concept from Persian and Arabic theosophical literature. This realm represents the ideas and representations that intermix being and becoming. In Corbin’s (translated) words, the imaginal realm:

possesses extension and dimensions, forms and colors, without their being perceptible to the senses, as they are when they are properties of physical bodies. No, these dimensions, shapes, and colors are the proper object of imaginative perception or the “psychospiritual senses”; and that world, fully objective and real, where everything existing in the sensory world has its analogue, but not perceptible by the senses.

To me, this idea of the imaginal bridges neatly with the constraints of intention. To intend, we must extend the information of our senses into their fullest hyper real, hyper relational representation of our being and then imbue that representation with all it could phenomenologically mean to us, that is imbue it with all the normative colors and flavors that representation could become. If we are to act with agency, we must then yoke that representation back into the constraints of our embodied capacities, choosing what we perceive should be from what we perceive could be.

It is in this realm of the imaginal that the ego minds must live. For the ego represents that cutting and ordering of potential value into enacted value better than any other concept I know of. Ego lives in the imaginal and pulls that realm of possibility back into objective reality through embodying normativity. The language of the ego is therefore intention.

Expressing our agency involves mapping where we believe we are to where we value becoming. Agency occurs through the forming of intention and the flow from intention into a cascade of actions. If we are to become better at inferring intention, then we must enhance our capacity to contextually identify who we are, where we are in relation to our environment, identify what and why we value, and how we map between where we are and our values in order to become more of what we value. Each area can be addressed separately, but improving all has synergistic effects on our capacities. Each of these elements—relating, valuing, and interfacing the two—can be improved through either further training our innate capabilities or through extending our these capacities through enhancement from external tools. The choice is not binary such that improving both is advantageous.

In either case, the focus of such enhancements must be to actualize improvements at the individual level. If we cannot model intentions relatively equally we are likely to lose much of our individual identities to those with far superior capabilities in this regard. When only privileged agents can model intentionality reliably, then the issues of gullibility I previously touched upon become unavoidable and that would likely result in large groups of people becoming disenfranchised from their individual autonomy.

In conclusion, because of the interconnected and pluralistic nature of our global society and due to the speed of our digital infrastructure, our reality is increasingly characterized by agency. The number and diversity of entities capable of acting intentionally that we must interact with individually and collectively keeps expanding. In order to navigate this landscape, we must be able to see it. The landscape of agency is characterized in no small part by the dynamics of how the intentions of agents interact with one another. The capacity to reliably infer intentions is therefore paramount to our continued well being. Our innate capacity for inferring intentions is saturated in the current landscape and we must actively try to augment and expand that capacity. Recreating or simulating intentions is not sufficient, nor is withholding augmented capacities for use by a select few, for that is likely to exacerbate the instabilities brought on by fear, distrust, and gullibility that characterize our society rather than ameliorate them. Instead, we must embark on a program to improve all of our innate capacities for inferring intention. Such a program must break the concept of intention into modular and legible subcomponents, otherwise our ability to teach, train, and incrementally improve our capacities in this regard will remain too limited to meet our needs.

I hope to work on this problem further, and purpose of this Substack is mainly to share what I’ve learned with as wide an audience as possible. If inferring intention is as important a skill as I make it out to be, then I can only hope that some of you may join me in this effort. Maybe together we can start to address this problem by carving it at its joints, and start to implement the frameworks that will enable us to pedagogically and technologically improve our individual and collective intention inferring capacities.